Those with equity stakes in the software business received regular windfalls, as the company split its shares nine times between its 1986 stock market debut and 2003. Microsoft’s shares rose sharply and steadily throughout the latter half of the 1990s, fuelling a corporation-wide obsession with the stock price, as staff watched their fortunes grow daily, reports The Telegraph.

It was easy for Microsoft to cream off the most talented engineers, creating a virtuous circle that helped the company maintain its position at the top of the heap. “It was the hottest company in America and it got the hot people. Microsoft was riding high,” says a source close the business during that era.

But Microsoft’s fortunes have since waned. The company faces increasing competition from its longstanding rival, Apple, whose sleek, shiny touch-screen products such as the iPhone and the iPad have diverted billions of dollars of consumer spend and rendered Microsoft’s static screens thoroughly passe. Meanwhile, web search giant Google has been squaring up to Microsoft in the so-called “enterprise” market, catering for businesses, where it is offering its Google email and Google + social network as an alternative to the longstanding Microsoft Office products that once had the market cornered.

Microsoft’s topple from the top of the technology hierarchy has had a major impact on the culture of the Redmond business. Executives describe a ruthless work environment, where more energy is spent on managing internal politics and unweildy bureaucracy than on creating new products. Its slowing growth has also made it harder to attract the tech industry’s best talent.

That is not to say it hasn’t made some brave moves, however.

Microsoft has spent the last couple of years forging a series of alliances to help it recover its form, for example striking a 2010 deal with Nokia to produce the first proper smartphones based on Microsoft’s Windows operating system. The mobiles have had a lacklustre start, such that Windows phones account for just 4pc of the smartphone market. Then, last year, Microsoft bought Skype, the company which allows people to make free video calls online, in a $8.5bn (£5.3bn) deal. Many analysts balked at the price tag, though Skype has enabled Microsoft to gain a foothold in operating systems other than its own, and has helped it to regain traction with younger users, for whom Microsoft had stopped being cool.

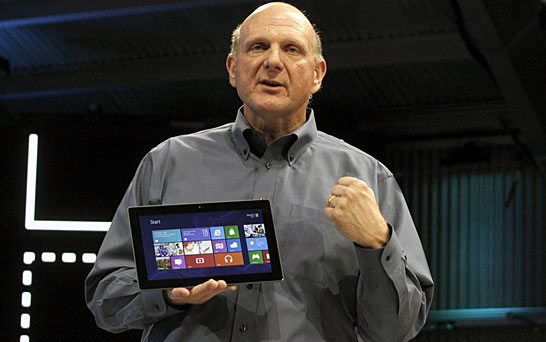

However, Microsoft’s real fightback will start later this week, when the company starts selling its new “Surface” tablet device and Windows 8, the first version of Microsoft’s staple operating system that has been designed with touch screens in mind.

The operating system offers a “fast and fluid experience” across traditional PCs and touch-screen tablet devices, enabling users to move seamlessly between them, Steven Sinofsky, president of Microsoft’s Windows division told a conference in Shanghai yesterday. “It’s a completely different feel. It’s clean. It’s beautiful. It’s intuitive,” he said. Those are words that would usually be more closely associated with Apple products, not those from Microsoft.

Bill Gates, Microsoft’s founder and chairman, told the Abu Dhabi Media Summit earlier this month that the company had finally hit upon the software that “combines the best of the tablet and the PC”.

Meanwhile, the Surface tablet, which will sell for £399 in Britain, is hailed as the first device that will enable Microsoft loyalists to make the most of the new Windows 8 software. It is lighter than Apple’s iPad, but also bigger, with a built in stand and cover which doubles as a keyboard and enables users to convert it into something resembling a traditional laptop when needed.

There are already some rumblings of dissent, however. Some long-term Microsoft fans resent having to learn how to use an altogether new system, whilst Carolina Milanesi, an alnalyst at Gartner, has warned that Microsoft must not sacrifice the usability of the new system for the sake of keeping certain “legacy” features going.

Even so, Friday’s double launch is regarded as Microsoft’s best chance of a comeback.

“This is the biggest bet that Microsoft has placed since the launch of Windows 95,” adds Ben Wood at CCS Insight. “It is showing that it can be more than just a PC company and moving into a new world where people use lots of different devices. It is absolutely essential to the future of the business.”

It feels unlikely that Microsoft will return to the heady success of the late eighties any time soon, but it is worth remembering the world of technology arguably has a contracted boom and bust cycle. At around the same time as the company’s Redmond workers were watching its share price tick up in the late 1990s, Apple – now the biggest listed company in the world today – was close to going bust.