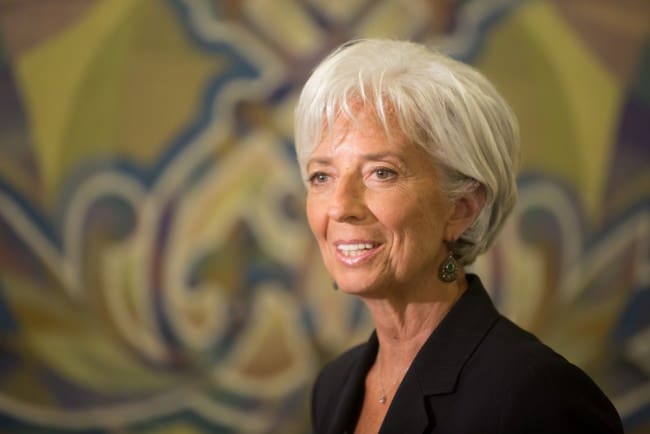

In an address to Goethe University, the managing director of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), said the political and economic establishment will face a crisis of confidence among the general public if it fails to address growing and legitimate concerns about inequality, reports CityAM.

Lagarde pressured policymakers to avoid temptations to respond to such discontent by pulling up the drawbridge and reverting to protectionism. Instead, she outlined a series of specific policies she wants countries to take.

Solutions for the low growth era included raising the minimum wage in the United States, better training schemes for unemployed young people in the Eurozone and a more vigorous push for diversification among low-income countries and commodities exporters

“We have made much progress since the great financial crisis. But because growth has been too low for too long, too many people are simply not feeling it … The good news is that the recovery continues; we have growth; we are not in a crisis. The not-so-good news is that the recovery remains too slow, too fragile, and risks to its durability are increasing,” Lagarde warned.

“Even if inequality on a global, cross-country scale has been declining, it is no wonder that perceptions abound that the cards are stacked against the common man—and woman— in favour of elites,” she added.

Lagarde, who was recently appointed for a second term as head of the Washington-based IMF, identified a number of risks facing the world economy:

- Advanced economies, she said, are grappling with “longstanding crisis legacies – high debt, low inflation, low investment, low productivity, and, for some, high unemployment.

- Emerging markets, meanwhile, were increasingly vulnerable to global developments, such as “lower commodity prices, higher corporate debt, volatile capital flows and – for some countries – de-risking and reduced bank lending.”

Dealing with such a complex array of factors requires a co-operative response from global policymakers, Lagarde said, with reforms needed in three areas: structural reforms from national governments, more “growth-friendly” fiscal policies, and accommodative monetary policy.

Lagarde, who has restored the reputation of the IMF during the financial crisis and courted strong relationships with the world’s finance ministers, did not hesitate to single out specific measures she thinks individual countries need to take:

- The United States should “boost its labour supply by expanding the earned income tax credit, increasing the federal minimum wage, and strengthening family-friendly benefits”.

- The Eurozone should “implement better training and employment-matching policies to help more people find jobs, especially young people”.

- For developing nations, Lagarde said “increased diversification is the name of the game”.

In advanced economies, Lagarde also wants to see higher spending on research and development. If private investment were to increase by two-fifths, the IMF calculates that economies would grow by five per cent more over the next decade. Such a policy, the Fund believes, would cost “around 0.4 per cent of GDP per year – partly achieved through improved public spending and partly through better-targeted tax incentives.”

She also identified several bright examples of countries taking sensible investment decisions to boost growth in the post-crisis era. These included Japan’s shift to help more women get into work, Germany’s plans to increase investment infrastructure and introduce a new tax relief for workers, and India’s stripping away of costly energy subsidies.