Wander around Dublin’s Grand Canal Quay and you get a sense of how successful the Republic of Ireland has been in attracting US technology companies.

Google has its international headquarters across a campus of offices and will soon have more space nearby at the Boland’s Mill development.

Just across the canal, Facebook has its international HQ with Tripadvisor and AirBnB close by.

Stripe, the United States-based payments firm, could soon be in the area.

Last month its Irish founders said they’re planning about 1,000 new jobs in Ireland.

The head of the country’s inward investment agency, Martin Shanahan, described the Stripe investment as a “phenomenal signal from Ireland and about Ireland”.

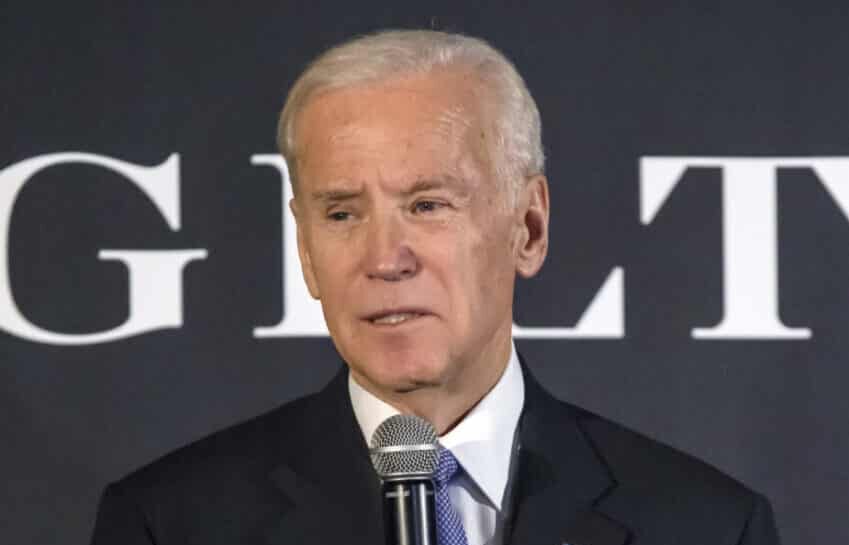

But there’s now a risk that the pipeline of investment from the US could dry up if President Joe Biden can lead a major change to global tax rules.

Irish tax advantage under threat

In among those tech company HQs in Dublin’s docklands, you will also find the offices of the lawyers and accountants who help US firms use Ireland’s tax system to reduce their global tax bills.

For the last 20 years Ireland has had a simple message: invest here and you will pay just 12.5% tax on your Irish profits.

That compares favourably to headline corporation tax rates of 19% in the UK, 30% in Germany and 26.5% in Canada.

It is an article of faith in Irish politics that the 12.5% rate has been vital to attracting US investment.

But that tax advantage could be seriously undermined if President Biden gets his way.

The most striking of his proposals – and the one of most consequence for Ireland – is for a global minimum corporate tax rate.

The US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has suggested a 21% minimum rate.

“We are working with G20 nations to agree to a global minimum corporate tax rate that can stop the race to the bottom,” she said in a speech last week.

“Together we can use a global minimum tax to make sure the global economy thrives based on a more level playing field in the taxation of multinational corporations.”

What would it mean for Ireland’s economy?

Essentially that would mean if a company paid tax at the lower Irish rate, then the US (or other countries) could top up that company’s tax in their jurisdiction to get it to the global minimum.

So if a US company had a presence in Ireland primarily for the tax advantage, that advantage would disappear.

This is a matter of urgency for the Biden administration because it is planning to raise corporate taxes at home and would prefer not to see more tax revenues leaking to other countries.

Peter Vale, tax partner with accounting firm Grant Thornton in Dublin, thinks a global minimum rate is now an inevitability.

“If you’d asked me six months ago I’d have been quite sceptical, there was a lot of opposition,” he said.

“But it’s now moving by the day and, with the US behind it with its plans, I think we’re going to arrive at some sort of global consensus.”

He said the key issue for Ireland becomes the level at which the rate is set.

“I don’t think 21% is where it will land, I suspect it will be somewhere in the teens.”

Other details will be important too: “Exactly how will you work out what the rate is a company is paying in Ireland and what does that mean in terms of any top up? The detail becomes pretty critical.”

The Biden proposals have reinvigorated work which is being led by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development), an intergovernmental economic organisation.

It began a project known as Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) in 2013, which aims to mitigate tax loopholes which currently allow companies to shift profits from higher tax countries to lower tax countries like Ireland.

‘Intention to target Ireland’

Perhaps ironically Ireland appears to have been a major beneficiary of some of the early outcomes of the BEPS project.

The country’s corporation tax receipts have soared from about €4bn (£3.5bn) in 2013 to around €12bn (£10.5bn) in 2020.

Seamus Coffey, an expert in Irish corporation tax, told the At the Margin podcast that this was because of the focus on what is known as “substance”.

That is the principle that companies should declare their profits in the location where they have real operations or activities.

“Countries like Ireland have been a huge winner from BEPS mark one,” he said.

“The objective was to align profit with substance and we actually are one of the countries where these companies have substance, whether it be pharmaceuticals, computer chips, medical devices and the ICT companies.

“I think when countries in the G7 looked at this they thought ‘that’s not quite what we wanted’ – maybe the intention was to target countries like Ireland, not benefit them.”

When could we see an impact?

In the next round of BEPS, with the US on board, those other rich countries are more likely to get what they want at Ireland’s expense.

But even if President Biden can agree the reforms at home and abroad, how quickly would that have an impact in Ireland?

Mr Coffey thinks any negative effects would not be instant because tax is not everything.

“Are the ICT companies likely to head off around the world, scattering their headquarters to various different cities?” he said.

“There are benefits to being co-located. At least in the medium term we are not likely to see a huge shock.”

That is echoed by the IDA (Industrial Development Authority), the inward investment agency, which points to Ireland’s workforce and significant clusters of specialisation in areas like medical technology and pharmaceuticals.

The IDA also sees the Brexit angle, pointing out that Ireland, unlike its UK neighbour, is part of the EU’s single market.

In a statement, it said: “Ireland is at the heart of Europe. Ireland’s continued commitment to the EU is a core part of Ireland’s value proposition to foreign investors, offering a base to access the European Single Market and to grow their business.

“Ireland also benefits from free movement of people within the EU, giving businesses located in Ireland access to a European labour market.”

The Irish government has been engaged in the BEPS process, though in a speech last year the Finance Minister, Pascal Donohoe, said he remained to be convinced of the need for minimum taxation, beyond the specific challenges relating to the digital economy.

This week a government spokesman said: “Ireland is aware of the US proposals.

“We are constructively engaging in these discussions, and will consider any proposals carefully noting that political level discussions on these issues have not yet taken place with the 139 countries involved in this process.”